Are We Still Able to Die?

Part One of Power as Reality: does power allow us any meaning in living and dying?

Power as Reality Introduction

This article is the first in what I hope is a series of articles that explore the idea of Power as the control over reality, or in other terms the control over how people experience themselves, the world, and other people and groups. This philosophical endeavor began after reading an interview with Foucault, Deleuze, and Guattari shortly after the release of Anti-Oedipus (1972), where Foucault states that we do not even understand what power is; even if we understand specific actualizations of power, we still have not gotten to the source of what power is. I want to offer a conception of power that is abstract enough to exist throughout all historical stages and all manifestations of power, whether in the pre-historic or the capitalistic, in societies of domination or hegemony, or in societies of dictatorship or democracy. From the most concrete form of power, brute force, to the most abstract, ideology and desire formation, the ability to create and manipulate reality is the basis of all power, as both the creation of the fear of one’s life in a direct confrontation and the hatred of men you have never met.

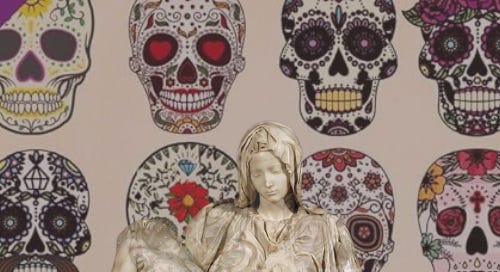

Death and the Symbolic

Most systems of power or individual manifestations of power throughout history have had to rely upon the threat of death to inflict their will upon those who are initially unwilling to follow their will. This ability to threaten one’s life is domination, or more specifically the ability to make one believe, regardless of its truth, that a person has a greater ability to inflict death than vice versa is domination. Baudrillard discusses this in The Agony of Power, a collection of some of his final essays, in contrast to hegemony, which will be discussed later. Domination is what most discussions of power have truly been about up to this point. It is a manifestation of power that requires a human relationship of master and slave or oppressor and oppressed to be clearly expressed and understood by both parties. While domination is more physically brutal than Hegemony, it provides a means of escape either through the realization that overwhelming physical power can overturn the oppressor’s power or, if not that, the oppressor still needed the oppressed, meaning the oppressed had power over the oppressor by sacrificing their own lives as a form of resistance. Resistance meant that one was still able to make the relation of power illegitimate even by the most drastic means, but death had a symbolic power that could inspire the living and make the threat of death that maintained a system of oppression null and void.

Hegemony has created an anti-body that perfectly fights against resistance to its system of power, its hold over reality is that nothing can mean anything anymore, even our deaths are symbolically empty. To fight and resist used to mean to challenge a former master as an equal in the field of the physical, now power is so abstracted in hegemony that there is no need for individual domination (though this still undeniably exists) for hegemony to maintain itself. A system run entirely on the economic thinking of pure calculation has found that the greatest threat to power is the possibility of resistance, and the possibility of resistance is found within the symbolic power of life and death. The anti-power that someone could care about others enough to mess with the efficiency of any part of the system had to be gotten rid of.

Death, however, is still a tool of power and hegemony as it has not forgotten that people still believe that death should mean something. Baudrillard’s discussion of terrorism and counter-terrorism seems ripe in this discussion but the problems of the symbolic power and anti-symbolic power extend to other problems such as school shootings and the discussions surrounding gun-control policies. Primarily, his discussions seem to center around the idea that death has power in hegemony as something that can evoke great emotional responses and great apathy. 9/11 being one of his biggest discussions, during this point of his theory, not only needs to be put in the context of the counter-terrorism at home, which he discusses in The Apathy of Power as allowing Americans to choose the authoritarianism of security as a response to the attack but also the apathy given to the hundreds of thousands of people who died in the military responses to the attacks. The last remaining aspects of the symbolic allowed to exist at the time (such as the abstract symbolic powers of American pride and patriotism) were used and personalized to create an infinite apathy for the suffering of other groups. The targets could have been anyone, despite the people actually responsible being a small, definable group of people, but the overwhelming emotion created in response to an event of terror was used to recreate terror for a group that the nation now had total apathy for. Seeking revenge through the creation of death for a group that was not afforded the right of being human, no number of Iraqi civilian deaths could mean anything for the average American until the war was seen as illegitimate by the masses, which by that point was decade or more years too late.

But now hegemony, especially the most right-wing parts of today’s power structures, wants an apathy towards any death that does not serve its wishes. Over and over we see school shootings that kill the children we are told to care about, but their lives and deaths are supposed to mean nothing at a political level. If they were able to truly die, their death would mean that we should think and change; these victims must be at best abstractly mourned through thoughts and prayers that do not actually claim personhood for the victims. The changes that would actually solve this problem are not in line with what this aspect of hegemony wants, there is no increase in surveillance or security that would benefit the system that could actually solve this problem; you can’t sell the true solution that society needs to change its relationship to weapons, masculinity, or mental health. It can, however, create attitudes that are efficient: you need more guns, hell the teachers need guns, and troubled people need treatment through therapy. This problem creates apathy because it wants us to believe we don’t have a problem with isolation and access to weapons, as both of these are the current things deemed efficient by calculative thinking; death allowing us to question if we should be living differently is an unacceptable answer to these problems.

Life and Death have always been the tools of power, now where power has little human elements remaining, death has become an unacceptable inconvenience to hegemonic power, to the point that allowing people the meaning provided in death is a threat to the system that is no longer allowed. Emotion and apathy are no more than tools that are manipulated toward specific areas and groups and used against others.

Reassertion of the Symbolic

The attempt to return to symbolic power seems to be both truly powerless but also mislead. Terror, in a lot of cases that Baudrillard discusses, seems to primarily be an attempt to assert symbolic meaning in life and death. As discussed above, acts of sacrifice of life, either through individual martyrdom or through terror, were a way of demonstrating a rebellion against a system of domination. While the source of this may be debated, hegemony can only allow two kinds of death: those that mean infinitely and those that mean nothing; neither of these can escape power as they are some of the tools it uses the most effectively. Either death provokes such a strong response that any level of violence in response is justified or death provokes such a neutral nullified response that caring about those persons is seen as disgusting.

Many post-structuralists (Deleuze, Guattari, and Baudrillard) who understood the problem of the collapse of the symbolic and domination and being replaced by a new form of power, also understood that this new power makes domination look preferable. This, however, can not be the case to advocate for. While the newer form of power in hegemony may seem inescapable without reasserting domination, this dichotomy may be at the center of why this kind of power has so much control over our views toward reality: we can have liberation of identity without the possibility of rebellion or domination with the possibility of rebelling against it. Part of my greatest disappointment with Baudrillard’s The Agony of Power was that it was positioned as if it was going to discuss in further detail the possibility of living without power, creating a society that no longer needs power through domination or hegemony. This is a theory I want to explore more in future articles that have more dialogue with Foucault, Bataille, Levinas, and Deleuze & Guattari’s works; the possibility of living without power through creating the possibility of living without the need for a symbolic beyond our own sovereignty. I posit that the theory we need to move past a system of power that uses meaning and lack of meaning against us and others is to create the necessary theory and forms of living to move towards the real.